The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

Study the chapter for one week.

Over the week:

Activity 1: Narrate the Chapter

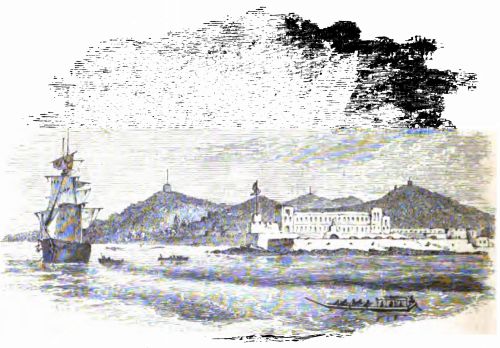

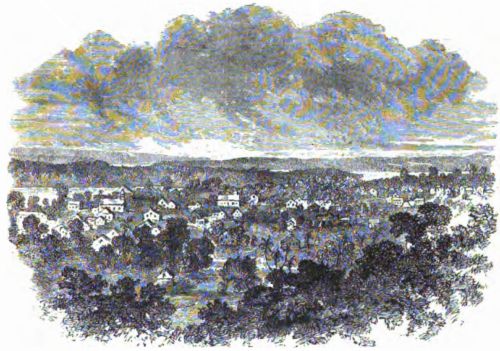

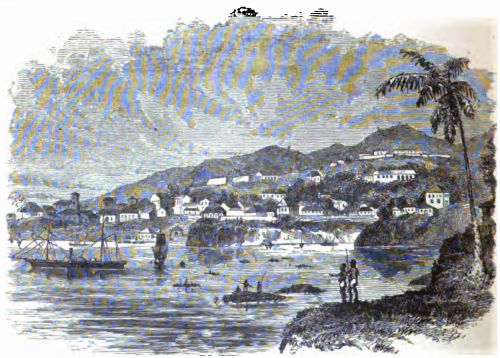

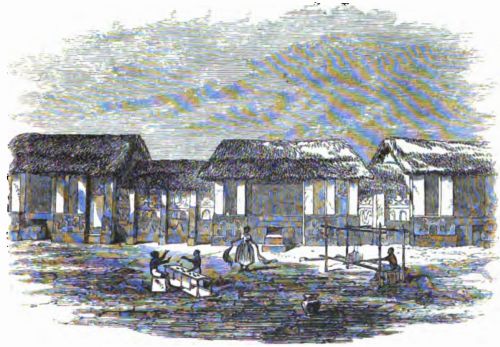

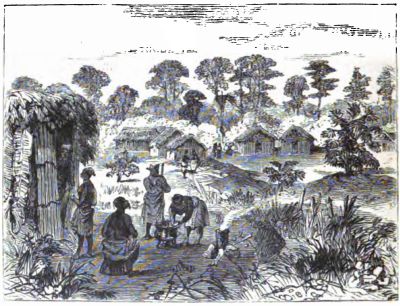

Activity 2: Study the Chapter Pictures

Activity 3: Observe the Modern Equivalent

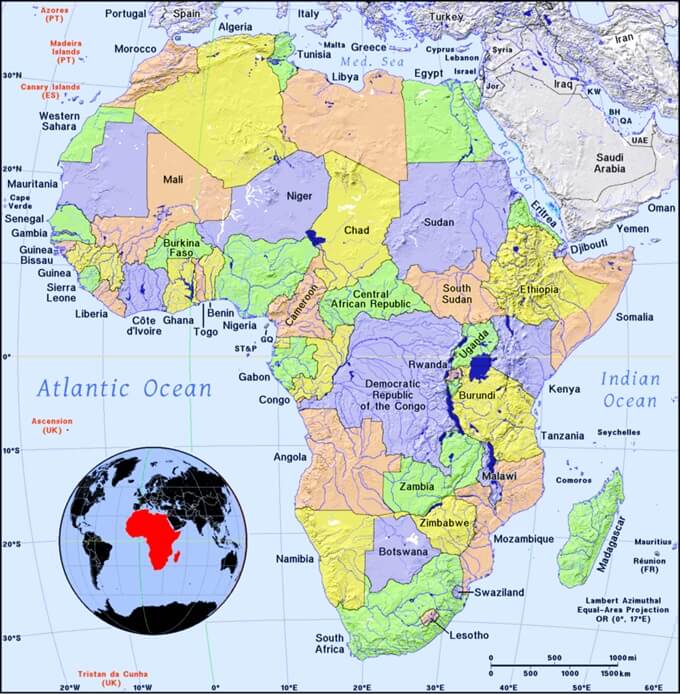

Activity 4: Map the Chapter

Find the following on the map of Africa:

Activity 5: Map the Chapter on a Globe